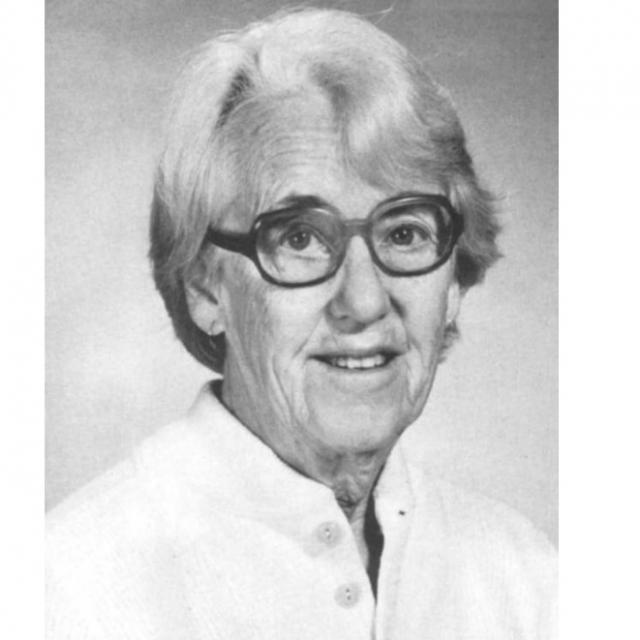

Bea Sweeney (19/50)

CCS was honored to showcase 50 individuals and activities during our 50th Anniversary in 2017-2018 to share our rich history. Take a look at the amazing people responsible for making our unconventional College possible!

In Memoriam

Eleanor Beatrice March Sweeney (1914-1989) was passionate about biology from as early as she could remember. Known as “Bea or Beazy,” to her friends and family, she did not take a formal biology class until she was a freshman at Smith College. Sweeney lived her “early scientific life entirely out of school,” she said in her 1987 autobiography. This included identifying and recording flowers around her New England home and attempting to create a bog in her backyard. Sweeney was revolutionary for women in science. Her college botany professors, she explained, “…were fine women, but they were all spinsters without private lives.” She vowed to be different—to be a scientist and have a family. “After all, men in science did not have to give up family life.” After College, she raised 2 children while attending graduate school. In her autobiography she recognized her graduate advisor who “…never in any way implied that I was inferior to his male graduate students. He quietly made it possible for me to continue my research during whatever time I could manage when I had my first child and then a second.” She and her husband Paul Lee Sweeney had 4 children.

She earned her Ph.D. degree from Radcliffe College (1942), working on hormone regulation of protoplasmic streaming in plant seedlings. Sweeney and her physician husband moved to San Diego after she earned her doctorate so he could become a flight surgeon during World War II. From 1948-1961, Sweeney was a research biologist at Scripps Institution of Oceanography where she began her studies of circadian rhythms (biological clocks) and their control of plant processes, including bioluminescence, photosynthesis and cell division, in dinoflagellate algae. Sweeney continued her study of biological clocks while a research biologist at Yale University from 1961-67.

In 1967—the same year CCS was established—Sweeney joined the Biological Sciences department at UCSB, becoming a Professor in 1971 and an Emerita Professor in 1982. She immediately gravitated to CCS and began teaching in the new College, where she developed the Walking Biology course, still being taught today. She served as CCS Associate Provost from 1978-1981.

According to many who knew her, including CCS Biology alumna and Nobel Lauteate Carol Greider, Professor Sweeney was instrumental in helping students pursue their curiosity and encouraged them to work with faculty. Sweeney was committed to teaching undergraduates at CCS, and took an active interest in every student that came to talk to her. “She always had a smile on her face, and it wasn’t that she made you feel important, it was the excitement of what is possible. I would just go to her office and talk to her because it was so interesting,” recalls Hank Pitcher fondly (CCS Art ’71; current CCS faculty). “She seemed to be interested in what I had to say, too. She was just so remarkably open and it was just fun for her to talk about it with us.” The biologist happily chatted with every student even if they were not in her discipline. “Their questions enlivened discussions and their ideas were an inspiration,” Sweeney wrote of students in her autobiography. “To teach such students is pure fun.”

Professor Sweeney was instrumental in helping students pursue their curiosity and encouraged them to work with faculty. Sweeney was committed to teaching undergraduates at CCS, and took an active interest in every student that came to talk to her.

Among her accomplishments, Sweeney published 139 scientific manuscripts. While she was a champion for women in science, she primarily was for any young person who had an interest, according to her eulogy. She advised women scientists to “keep their maiden names, dare to be assertive, and refused to be discouraged.” Sweeney encouraged women (and young men) to pursue both a family and career in science. She said, “It may not be easy to combine a scientific career with family but it can be done and it’s worth all the effort.”

She served as president of several scientific societies and was formally recognized with honorary doctorates from several universities (including Umea University in Umea, Sweden in 1985 and Knox College in Galesburg, Illinois in 1986). She was also a National Lecturer for the Phycological Society of America (1983-1984), and a recipient of the Darbaker Prize from the Botanical Society of America (1983).